FRACAS.COM

Table of Contentswww.fracas.com

Hadrian's Time MachineBy Brian Buchanan [Visit Emperor Hadrian's Wall in the UK and time travel back to Roman Britain] |

|

Warm sun lit the green, sharply undulating fields, drawing curves, corners and stones, as light and shadow fell away at a thousand angles. I stood precariously atop the shattered remnants of a great wandering wall. The stacked rows of smooth, rectangular mortared stones, remnants of ancient magnificence, disappeared into the horizon both east and west.

This morning, we had driven north from Windermere, that renowned lakeside village in Cumbria, out into the rolling desolation of English border country, in the very middle of the upper throat of the island. We had joined the A591's rush hour flow to the edge of Kendal, then took to the A6 north to the outskirts of Penrith. We had then swerved gradually eastward into the sparsely inhabited middle kingdom of the border counties of Cumbria and Durham. The A69's narrow track then took us through undulating hills, bare of trees, sparse of grass and richly covered with rocks and sheep. We were on a quest for Hadrian's Wall.

We were now in the prime area for viewing one of the most dramatic remnants of Roman Britain: the areas fifty miles either side of Hexham. Following the B6318, a small, parallel road tributary of the A69, took us close to our objective at several points. The traffic on this skinny, rural track edged with high grass was close to as fierce as the afternoon sun. In our stops on the wall, we were very far from alone. Adults from every corner of the world were in multitudinous attendance, as were the ubiquitous hordes of British school children.

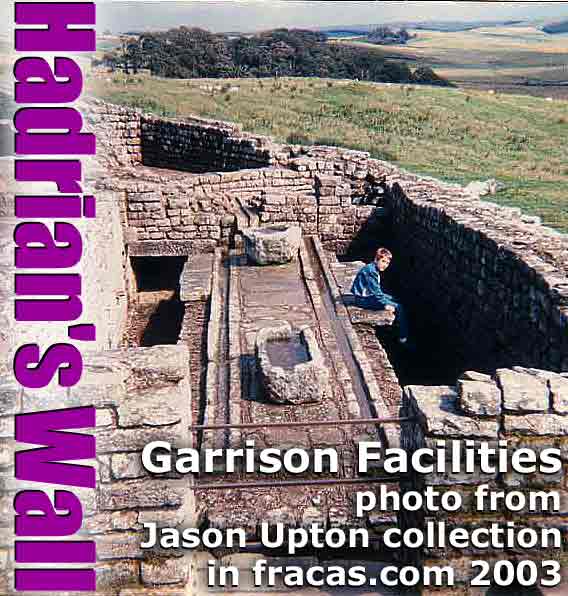

As I perched contemplatively at the top of a high wall on historical site now called Housestead, eyes feasting on the relics of a town built into the wall itself, I speculated about history's footprints on all our lives.

I couldn't help but think of alien invasions. Back in 40 A.D., the local denizens of this sparse, rocky and infertile northern border area must have felt a good deal like the characters portrayed in several recent movies, perhaps such as those exemplified by that mawkish tribute to U.S. patriotism, Independence Day. The Romans came, and they left, but nothing was ever the same again.

Picts, Celts, Scots and assorted other northern tribesmen must have lived in wonder and fear of a powerful culture with technology, arms and customs light years ahead of theirs, and so implacably, smugly superior that they must have feared for their survival. Invaded several generations before by the Romans commanded by Julius Caesar, and pushed over militarily at every contact with Roman legions, in the Year 43 came the beginning construction of the wall on whose remnants I now stood. Finished in 100, the wall took on alterations over the next 200 years, until the Romans left in the mid-3rd century.

Luckily, genocide was not on the Roman agenda. In the alien analogy, the Romans were like the Borgs from Star Trek: assimilation was their game. Resistance was probably not entirely useless. But based on evidence of Roman Britain, here and at thousands of other sites on the island, resistance was silly. Romans seemed to have a better, more peaceable idea about how to make most things work. Pre-Roman Britain was a brigand's refuge for much of continental Europe, carved up by primitive warring factions whose sense of nation was 500 years away. When the Romans left or at least abandoned their garrisons after 300 years, to such a chaotic state the island returned. And memory of their time blew away in the medieval turmoil and cultural decline that would follow.

In fact, this magnificent ruin remained an obscure curiosity until the 19th century, placed as it was in the wild and wooly border country whose politics and local citizenry were not pacified, nor the area much settled, until the 18th century. Yet in those early years, an incubus of civilization must have given root to civilization that survived all those benighted centuries intervening. Every contact with remnants of Roman hegemony invites speculation about permanent impacts that such a regime could have had on the tight little island's longer term future, regardless of the ultimate fate of the great empire.

Hadrian's Wall, named after the emperor who ordered it, provided a symbol of Rome's control of this backward, savage island. All of it. Contrary to myth, the wall did not represent a line of defense, but simply a convenient, narrow, 75-mile neck of the island to consolidate lines of supply from the southern towns and the relatively unimportant north. Whenever the legions chose, they ventured north of the wall relatively unopposed, superior as they were in military organization and numbers. They marched right on up to the top of the British island at John O Groats, scattering resistance in their wake. The wall is more hubris than haven. While most of it is gone, along with the garrison towns built into it in intervals, Hadrian's wall still makes a statement about the complex sophistication that disappeared from human ken for a millenium and a half until Christianity's dark stranglehold on western culture finally abated in the Renaissance.

But what a menacing, yet enthralling spectacle that pre-Christian culture must have been. Round these ruins one senses the magic of a lost greatness. One can almost hear and a see what must have transpired here in these lonely marshes and valleys those many years ago. The mystery of those times still engenders speculation. Soldiers in steel and leather on horse and on foot. Herders. Glowering traders and hunters watching from hill tops. Wagons and sledges hauling rock and other material. Wood-roofed stone buildings housing Roman stables more transcendentally more luxurious than indigenous wattled huts and holes in hills. Ordered bustle of the straight roads and water systems. What contrasts in culture there must have been. And what opportunities for learning.

Roman building technology is still not understood by modern engineering. How did their mortar hold together so well? These folks had central heating. Sewers. Water handling systems. Some wags claim the British haven't yet fully rediscovered these things. Those of us used to budget or even moderately priced British hotels have a dark, cheeky temptation to subscribe to such rude observations. Technical organization for quarrying stone, transporting materials and goods, running infrastructure for roads, mail... how could they do it, using almost entirely conscripts or new Roman citizens from the provinces now in Spain, Africa, the middle east, Eastern Europe or from Britain? What persuasive powers imperial Rome must have had, coming from a relatively open and tolerant but breathtakingly mighty society? What a powerful feeling of belonging must have accompanied the realization of being part of this empire, and to be a free citizen, soldier or even servant of a culture with such gravitas.

In the summer air, even among the hundreds of tourists roaming the desolated remnants of the main wall and that of the Roman town beside it, one senses the host of mysteries of this place. Who were these people? How could they do this? What happened that could cause the wall's abandonment to so many hundred years of ignorant neglect? Clearly that sense lures thousands of tourist to various points along the rows of stones each year. The wall, like all great relics of civilizations with dramatic features more spectacular than our own civilizations, is a time machine.

On a hot summer July, one's imagination whirrs back two thousand years, straining to picture the scene then through the eyes of those on either side of Hadrian's edifice. The wonder of it makes the crowds and traffic fade into faint background. Well, maybe not completely. Summer is a busy time. However in this area, rain and windy cold are common companions, so a visit in the fall or spring might avoid the crush, but raw weather might impose a bit more harsh realism about the border country than one might relish.

Charlotte and I came to the wall on this sweltering day as a minor pilgrimage. Twenty years earlier, we had spent six weeks on the road in Britain, running from Land's End on the southern tip to John O Groats on the northern nose. In mid-trip we insouciantly pointed our car at Haltwhistle, entirely because the name attracted us. We heard of the wall in a friendly pub, and recalling some dim memories of high school history, we drove out to a section of it running across a farmer's field. That opened our interest in Hadrian's old stone artifact, and provided a touchstone excuse or reason for our return to the region two decades later.

There are many ways to attack the wall as a tourist. Driving along it is most popular. Some walkers cover the entire length, camping or hoteling along the way. Still others engage guided walks with support vehicles for night-time hotel transport. The stones peter out near Newcastle on the east coast and Hadrian remnants aren't easy to find on the west side, either. Even in the sparsely peopled middle, where less of the wall fell victim to dismantlement for local construction, the quality of the remains do vary considerably. In some places, the wall is down to ground level, having provided building supplies for many centuries. In other places the wall is perhaps half intact, and perhaps two or three feet of Roman town walls still remain, as they do at Housestead. However ravaged, pirated and ruined by natural and human predations, enough remains to make Hadrian's time machine an evocative relic of Roman Britain.

Good walls make good neighbours, American poet Robert Frost claimed. About 19 centuries before Frost penned his words, a civilization raised up its rocky claim to supremacy over ancient Britain's landscape, perhaps suggesting that good walls do at least make lasting impressions.

© 1997-2002 Brian Buchanan, Vancouver, Canada

e-mail buchanan@fracas.com

[ This travel article first published with Provenance Magazine, ISSN 1203-8954 - Vol.2 No.3 ]

Brian is a well known freelance writer and business consultant who resides in Vancouver, B.C. Canada.

N.B. Publishers note: Brian Buchanan has been contributing to a number of online web magazines since 1997 including Provenance the web magazine for information professionals / Fracas.com and / eTRAVEL.com

· FRACAS the web publication home page

· Reference sources

· Media resources

· Credits

· Freelance writers

· Freelance editors

· Freelance publishers