Burgundy By Barge: Green Water, Red Wine - or -"French canal boat holiday"

Folding out of the odd-shaped and nautically inevitable too-short bed, a quick splash in a tiny sink, and one shuffles down the corridor toward dim, diffused light from the cabin at the back of the boat. Our 15 metre canal cruiser lies quietly at misty anchor alongside an odd collection of fellow-travellers. A 6 metre, canvass-topped boat carries a French couple and their 5 year old daughter. A 30 metre steel canal cruiser holds a rich type from England. Two tourist canal cruisers similar to ours berth nearby. First up, I take the key from the ignition of the inside cockpit dash, brushing back the curtains and sliding open windows port and starboard. I light the propane stove, begin water for coffee, and throw open the back door and climb half up onto the roof deck with its upper cockpit. The boathook, deck chairs and life preservers and umbrella are where we left them, glimmering with morning dew on the white fiberglass of the open upper cockpit and deck. Of course they are. This is rural France: property lies out everyone on docks, in yards and in streets, untouched. But big city habits die reluctantly. Across the square cove of the boat basin and canal beyond, the familiar sight of middle-aged fishermen greets me as does his languid hand lifting up from one of his three poles propped at the canal bank. On the hills that give shape to the town, a medieval cathedral's two spires catch the day's early light. Further out, the green rolling fields of grain and hay come into focus. Looking closer to the boat basin, my eyes catch the dewy glint from the cobbled streets, as a few strollers and cars join the early motor scooter traffic on its way somewhere. Looking back down the canal, our highway through this bucolic heaven, I glance backward at dual green columns of tall trees grating the morning light into disparate strands, and casting odd and myriad shadows on the green-blue waters. Two bicyclists cruise by. Then a couple of cars, in a typically French relaxed, insouciant hurry without urgency. Just up the street the Super Marche's dark grey tar and gravel roof and gleaming orange walls and parking lot filled with shopping carts adds a modern aspect to the town. This is Day Six on our ten day journey into the eastern heart of France. We're about to depart the ancient walls and sights, sounds and culinary allures of Tonnaire. We are about 30 locks and 60 clicks into a journey that will take us from Laroche Migenne to Venarey, with a small detour westward on the Yonne River toward Auxerre. We made the detour to get a sense of travel on the wider, less uniform river, and to visit one of oldest and most beautiful medieval towns in France, called Joigny. Six of us set out to explore rural heartland of Europe's favourite destination country, on the liquid, languid back of waterways built two centuries ago for commerce not yet served by railways. While still open to commercial trade, and dotted by occasional large manufacturing plants, Le Canal de Bourgogne as we saw it in our ten days' journey seems to have slipped into arterial semi-retirement as a tourist playland. While travelling the straight and fast-flowing roads of France is certainly one kind of excursion paradise, canaling is quite a laid-back other way to discover La Belle France.

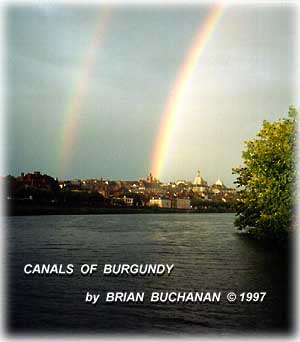

Travelling high watered, thirty meter-wide canals through fields and villages, while gazing into the rural backwaters and villages in the distance provides high leisure more than high adventure. Yet canaling in France provides visas unmatched by road or train travel. Wildlife springs or flies up in front of you: birds and water-creatures of various kinds, large cranes and other birds erupt into the air and water-rats scurry for their canal-bank holes.

As first up on this morning, I set off up the parkway alongside the canal for the village street, turning off just before the bridge, heading along a narrow, closely curbed street to stooped stone buildings containing an assortment of residences interspersed with a few shops. The second shop, beside a candy store, is the cynosure of early morning France: the baguette bakery. After the merry bonjours on both sides, I assay my powers of the local vernacular. "Deux pain, s'il vous plait. A voici." I'm pointing and gesturing at this point. It's just about as good as my French gets. And it's enough. "Oui, merci, messieur." The pleasant lady, strangely enough, considering the temptations, is not porcine at all. She tells me how much, which I manage to barely understand, but she shyly scribbles the sum on a piece of wrapping paper, and I am off my embarrassed hook. I pay her, sing out the au revoirs and trudge off back, enveloped in the breath-taking smells of fresh French bread. By the time I return, my companions are up. There are six of us. Three couples. Two pairs from Canada. Another from New Zealand. We are all travel veterans, but none have holidayed via canal before. After the usual breakfast and banter associated with making a home among friendly strangers with alien ways, we set off.

Since we face the high walls of the lock as we enter rather than entering the full as opposing traffic would, we must throw our front and back mooring ropes over the thick steel mooring posts from a boat deck several meters down in the lock's hole. That requires minor acrobatics. As the vessel chugs into the open lock, facing a closed front gate, one of us would move to the upper deck, toss the boat hook onto the lock's rampway or lawn, and grab the steel ladder indented into the concrete wall of the lock, swing up onto the lock top. Another crew member would thread the front mooring line to the hook and the ladder climber would toss the line over the front post, and with his boat hook, move to the back and do the same thing with the rear line. Then he would move the rear lock gate, closing one side while the keeper did the other. Then everyone waits for the fill-up. Once full, one of the vessel crew would open one side of the full lock, the keeper the other, and off we would go, various of us climbing on the departing vessel as it moves slowly out. Often the departing crew would rejoin the vessel clutching wine, fruit, preserves and condiments such as mustard, bought at stands at the lock. We often shopped while the lock filled. And so lock travel would go. In our 120 kilometer journey, we did this about 65 times. Somehow, it never grew boring. Although occasionally amusing. While none fell in, some situations were close things. Jumping from the vessel top directly to the top of a particularly low lock occasionally became a close and teetering thing. Finding ways to throw the mooring lines from vessel to shore could take on odd turns. Once or twice we lassoed the mooring stanchion. A few tosses to the onshore scrambler left the line in the lock drink. A few days into the journey, embarrassed into ingenuity by wet and lost rope ends, we began using the boat hook as line transporter between ship and shore. As we became more seasoned, we also took on more work at the lock: we helped close gates behind us, just as we had helped open the one side of the lock as we departed from a full lock. Sometimes we became confused, closing locks without tying up fore or aft or both, or going to the lock so fast that the line bearer couldn't catch the ladder to get off, and forcing the vessel pilot into a panic reverse at half throttle to stop, while the rest of the crew tried to figure out a way to get a line or two to shore to avoid the skewed bouncing the inevitable onrush of lock water would bring. Fortunately, we didn't break anything on shore or on board, but the sometimes precarious procedures provided all with plenty of laughter. Often in our salty reviews of these incidents brought up the paradigm of the five New York housewives that our boat rental representative told us about. These paragons did their fifty lock journey in a week, covered barely 100 kilometers, burned a thimble-full of diesel and declared that the experience was the best holiday they ever had. If they could manage, why should we worry? Certainly we were having a giggle about it all. Which was the point, after all. Between locks lay cruising. Lovely country sights. Lunch on the deck. Stops for country excursions, sometimes for long walks to abbeys and country houses famous for their splendor. On occasion, a beer and a gigantic plate of pomme frites would take the edge off sore feet and dry throats. The banter with local customers was inevitably friendly, if often semi-coherent, since our French was pretty much stuck in the "une petite peu" stage. At night, tied up to a boat basin, or simply tied to trees or mooring spikes along the canal, one would be tempted into the local villages for wine and beer at local bars, or later in the evening to restaurants with incongruous formality and pomp, at least by North American senses. But always the staff offered friendly service and formidably delicious food. While the chefs of these havens of civilization were serious people, inevitably their young staff, quite often young women, would crack their serious mien in the face of our fractured French, strange questions or our reactions to the food we received. The region where we travelled seemed a culinary hotspot for exotic meat dishes and pate. Dairy and grain farming seemed to dominate the agrarian economy, rather than, say, wine growing. Still, here as everywhere in France, wine was cheap. We often bought bottles for less than 10 francs. Colourful and charming towns were our quarry, and we found them. St. Florentine's ancient buildings and winding streets diverted us for hours. One recalls Montbard's castle turret up above the town's skyline, and remembers the six kilometer trek on quiet and lush country roads, with barely a lane to tread, up to an abbey that turned out to be closed. Special expensive tours were not to start for several hours. Bad information from the village's tourist information official? Gallic shrugs all round. We muttered mild recriminations on our picnic perch on a log beside the beautiful park beside our destination. Then we drank some bottled water and wine, and set off back to turn, abbey unexplored. Next time. Maybe. Then we trek good-naturedly back to Montbard's outskirts, there to binge on beer and a gigantic plate of pomme frites. Every village had scores of quiet roadside taverns or restaurants. We visited more than our quota, as we took refuge from kilometers of walking on cobbled and steep streets. Sometimes village names inticed by their very sound and look. Brienon sur Armencon, Flogny la Chappelle, ncy-le-Libre, Riverieres ... these are glorious names! Finally, our two penultimate bergs: Pont de Venarey and Les Laumes, both a little way off from the canal itself, and invitations for rainy walks for food and wine. Had we continued our progress we would have gone on to such places as Morigny-le-Cahouet, no doubt lovely too. However, the next stretch of 12 kilometers had 36 locks. We took a satisfied- for-now pass, and parked our vessel at the bridge nearest Venarey. On our last day, we left our last Burgundy restaurant late at night in a pouring rain, hid under the cover of gas pump canopy of an abandoned filling station, taking a picture of nesting dove watching us from six feet above our heads, and waited for rescue. It came in the form of a smiling cab driver contracted to drive us the next day to Montbard, some 10 kilometers away, to catch the bullet train to Paris and London. It was the perfect symbolic experience for the entire ten days: good food, physical exertion and discomfort turned to amusing incident. And, of course, French gentility rescuing us from the worst of the experience and leaving us in soaked laughter back at our vessel. As we plunged down the tracks at 300 kpm on our way to Paris' Gard du Lyon, thence to London via the chunnel, we all vowed to do it again. But not next year. Such a rich experience would need a few years to savour. And save up for.

|

· Freelance writers · Freelance editors · Freelance publishers |

||||