FRACAS.COM

Table of Contentswww.fracas.com

First lights and last stands: Custer and the Indians Together Again

[ historical and cultural perspective on the Battle of the Little Big Horn - American folklore & myths ]By Brian Buchanan

freelance copywriter

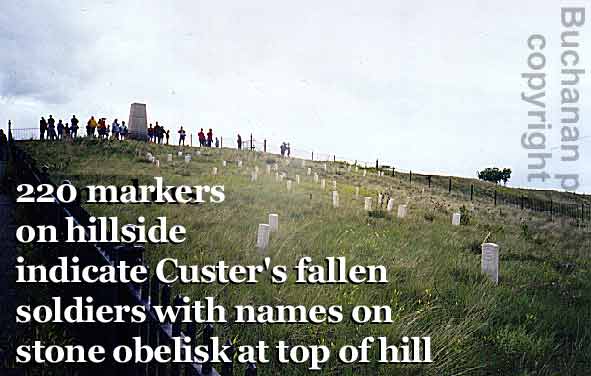

Two hundred and twenty markers climb the hillside toward a flat peak, while a glowering sky lurches and spins beyond. Along the edge of the meandering groups of tall, rectangular wooden markers runs a road. At the top, a 15- foot obelisk's stone sides bear the grave site occupants' names. A wind-driven rain bites at our faces and lashes the long grass across the rolling hills, painting light and shadow through a dozen hues of green landscape.

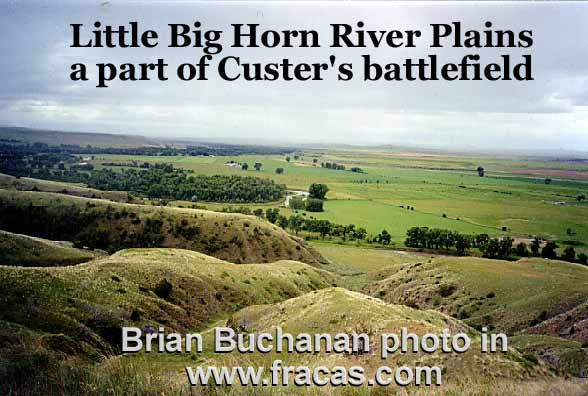

Turning my back to the wind, I look southward down a four- mile series of descending slopes to the Little Big Horn, clothed thickly in a border of 30 foot deciduous trees, and winding across the scene in series of sharp twists as it disappears out of sight across the undulating prairie. Westward, more white markers dot the grass-clothed hills: one or two in a clump, off into the distance. Up on a bluff ringed by sloping hills much like the one on which I stand, poke out more grave markers. And from that distant hill, down to the river at the west side of the trees, yet more markers. The sense of distance is surprising. Unlike Hollywood's version, the real 1876 drama took place over considerable distances, and as we found out from our Crow "interpretative center" guides, the battle took several days, not hours, to play itself out. That's two of a number of surprises I found at this lonely reach of national park in south-east Montana. Much of the truth about this battle runs against popular myth.

Looking up this 200 foot, 15 degree hill, I'm struck by the finality of the scene. Custer's last stand it was. The Cheyenne's and Lakota Sioux's too. While a minor skirmish in the 300 years of friction between various stone age aboriginals and sundry civilized and barbaric European factions, it was just about the last round of that cycle, though "Indian wars" lurched on intermittently for another 15 years. From King Philips' War in the original 17th Century English colonies, to the final Apache surrender in the South West, various aboriginal and European groups combined with each in fights with myriad enemies. In the most pivotal stages, the French and English used tribal alliances as they fought for control of North America in the Seven Years' War ending in 1763 with French withdrawal. But the carnage continued.

History is more complicated than modern political correctness would have it. Like many other early groups in North America, the Sioux and Cheyenne fought wars of extermination against other aboriginal groups. Alliances among groups were fleeting and fluid. Before the Europeans arrived, many tribes had already disappeared in the maelstrom of internecine wars following four separate waves of pre-European immigration from Asia to North America. When the Europeans arrived they found many willing allies. The Crow threw in with the blue coated United States cavalry to save themselves from extinction at the intruding Lakota's hands. Some 50 Crow died with Custer. In fact the Custer debacle's original purpose lay in driving Cheyenne and Lakota off lands designated by the US government for the Crow. In perhaps an incongruous case of constancy, considering how much one hears of broken government promises to aboriginals, the land is Crow property to this day. Our narrating guide is an eloguent Crow woman with a wicked sense of humour about snakes "right behind you" and about historical anomalies: "Crazy Horse would have come up right near that freeway...&148; of course, the freeway wasn't there then..."

On all sides, the warrior tradition was glorious and self-sustaining, regardless of practical considerations of property and assimilation. Bloody Knife, Custer's chief scout was a man of gravitas because he was a killer and leader, just as was Custer, Sitting Bull and the rest of the famous names of American folklore. Looking back, all the martial puffery seems ghastly to the modern sensibility, but that warrior tradition played a dominating role in driving so much of aboriginal history to its pitiful state today. Complicated? Room for blame on all sides? You bet. But fascinating drama it seems now, particularly as I stand imagining the feel and fears of those two days of battle between factions of men on horseback and on the ground, pursuing and killing each other with primitive clubs, knives, pistols and rifles, bloodily and up close.

So how did Custer come to this sorry, inglorious end? With 600 men, he came upon the Lakota and Cheyenne village down on the Little Big Horn, a temporary gathering of nomads for a conference on how to deal with the increasing blue coat activity and interference in their intertribal wars. Custer's scouts suggested there were about 2,000 people in the village. That would be men, women and children, since nomads took their home and families with them. Custer's arithmetic, based on numerous skirmishes, would calculate no more than a 1,000 warriors, probably fewer. In fact, there were more than 10,000 villagers, providing perhaps 4,000 warriors for the conflict.

| A sidebar about arms: Custer's men had state of art Sharps carbines and new Colt 45 revolvers. Their rifles were accurate up to 300 yards, and could kill before aboriginal arrows or shorter range lever action or older firearms could reach the Sharps shooters. Still, in a mobile battle and where numbers were so one-sided, Custer faced a tough situation. |

The site and its custodians describe the fascinating complexity of the battle. Custer had a rendezvous he chose not to keep. He made a fateful error in splitting up his troops, and in telling Major Keno to attack, instead of waiting for General Crook. He sealed his fate in mistakenly thinking the Indians had seen him... and so the drama plays out in its recounting, on these wind-swept ridges in Montana's south-east.

Looking for Custer's Last Stand? Some 55 miles east of Billings on Highway 212, the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument lies on the Crow Indian Reservation 60 miles south of Interstate Highway 94.

[END]

Copyright © 1999 - 2002 Brian Buchanan Brian can be reached by email

at buchanan@fracas.com

Brian is a well known freelance copywriter and business consultant who resides in Vancouver, B.C. Canada.

Brian's previous travel contributions to Provenance magazine have included topics such as Hadrians Wall in the United Kingdom, and

Barging through Burgundy a canal boat holiday in Burgundy, France.

N.B. Publishers note: Brian Buchanan has been contributing to a number of online web magazines since 1996 including Provenance the web magazine for information professionals / Fracas.com and / eTRAVEL.com

· Freelance copywriters

· Freelance technical writers

· Freelance editors

· Freelance publishers

see also

· Monroe County Library special collection

· National Park Service Little Big Horn site

· Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association